It is said that the Inuit have fifty-two words for snow. I don’t them, but I readily believe it. Snow is as varied as the clouds they come from. For instance, snow has a sound. When temperatures drop below -10 C, the snow no longer melts if it is compressed. That means that when you walk on it, the ice crystals themselves rub against each other making a kind of creaking noise. When temperatures fall further still, around the -30 C mark, the sound of ice crystals rubbing each other become more of squeak than a creak; it is a sound that is at once louder and more delicate than the creak of mid-level cold. Snow also has a silence. When the temperatures are closer to the freezing mark, around -3 C, the snow crystals melt together. This produces storybook snowfalls. Each flake (which is actually a fluffy collection of flakes) is a little pillow that muffles all noise so that even in the midst of a busy city, one hears nothing but silence all around. The opposite is true of frigid clear-skied cold. At -35 C, with no wind, sound travels far and clear. Noises themselves develop a kind of glass-like clarity, as though the soundwaves themselves have been turned to crystal, a sharp but thin kind of sound. One can often see the ice crystals in the air. They form a halo around the sun. On a cold sunny morning, the air itself sparkles with thousands of dazzling crystals.

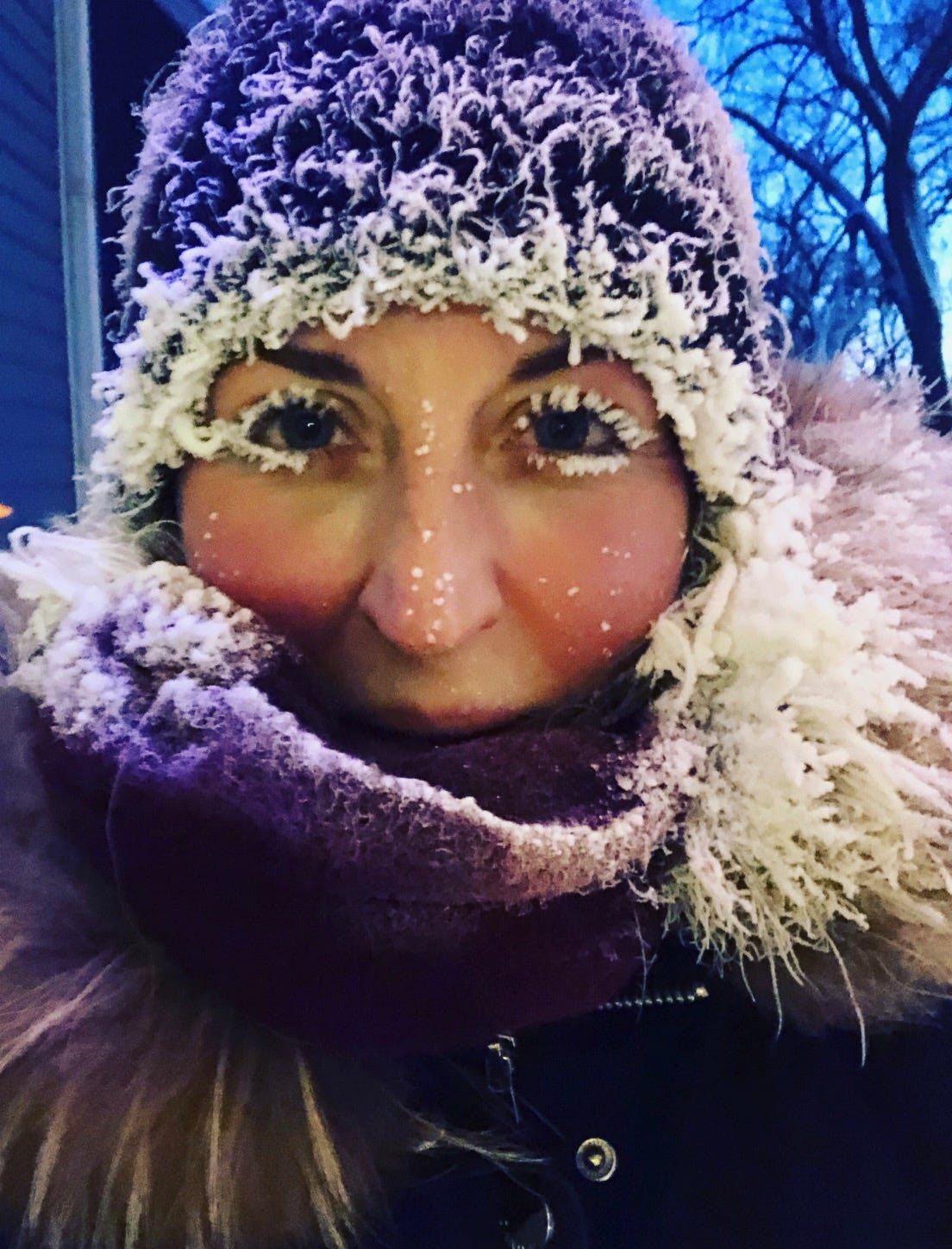

When the mercury drops below -30 C, body parts freeze quickly. The first thing to go numb, strangely, is usually one’s thighs. Thighs almost never get frostbite, but the tops of one legs go numb, sometimes within seconds. I suppose this is because the act of walking itself produces wind on the legs, and in the cold, wind is not one’s friend. If you’re not wearing a hat or mittens (mittens are better than gloves), your fingers or ears can freeze within minutes. It begins first with discomfort, then pain, then numbness, then – the danger zone – no pain or numbness at all. Flesh dies. The coldest air temperature I’ve ever experienced is -42 C, which is -43 F (at -40, Celsius and Fahrenheit meet). At those temperatures, the air takes on a kind of lunar quality. It is painful to inhale. One’s eyeballs hurt. If there is a wind at those temperatures, a windchill of -45 C or colder, frostbite can occur within around one minute. Air itself feels hostile. Wind has malice. The bitterness of the cold feels personal.

But the cold is not personal. It is worse than that. The cold is indifferent. The wind is under no obligation to make me feel comfortable, welcome, or safe. In everyday life I can see that I belong to a civilization that is designed around convenience and comfort. But the cold reminds me that the world owes me nothing. The number of inalienable human rights I am born with is precisely zero. What right does the wind owe me? Here I discover an awful idea: the world I inhabit does not exist to keep me alive. Indeed, the world doesn’t even know I am alive; it will offer no succor for me.

Awful is right word for it. When the cold dips to these polar temperatures, one feels awe, both fear and wonder. Unlike the balmy June weather which seems to be perfectly calibrated to my comfort, when the wind feels like a soft caress and the suns’ warmth like a lover’s embrace, the cold exists as a hostile presence to my body. I am certain that the world is not formed with me in mind.

Yet it is precisely because the cold is so alien to my warm bloodedness that I feel this fear and this wonder. In the cold, I feel my body as a separate thing from the world around me. Separate and vulnerable. The definitions of my form take shape. My limit becomes clear. I end at my toes and my fingers and my earlobes. My torso is an enclosed thing. I breathe. My breath is something I can hear and see.

In the cold I am reminded that Mary Shelley ended her masterpiece in the frozen wastes of the arctic. Frankenstein is about the horror which results from the unrestrained motions of the human will. It is about transgressing the limits of human power over the body. It seems fitting that Victor Frankenstein and his creature find their limit in the ice world, for the ice does indeed put a curb on human action. Frankenstein is narrated through the diary and the letters of Captain Walton, an Englishman who aspires to explore the north pole. His ship gets stuck fast on the northern sea ice. It is in the aloneness of the frozen sea where Walton encounters Victor Frankenstein, who is traveling north on his dog sled in pursuit of the monster he created. Frankenstein is near death with cold and fatigue. Frail, he is lifted into the ship which is held fast by the ice, and there he recounts to Captain Walton his tragic tale.

The story is well known to most of us. Shelley is able to maintain sympathy for both the doctor and for his creature, and also for Walton who risks the lives of his sailors in single-minded quest to explore the regions of the north. Frankenstein and Walton are kindred: both value the triumph of human power over nature, of human will over human limit; both desire to be set apart from the ordinariness of being human. It is a story of courage, of the individual, and of human striving.

Yet we should remember that Frankenstein is a horror story. “Oh, Frankenstein,” laments the monster, “generous and self-devoted being.” Frankenstein is a creator, in that he is generous, the originator of a life. But he is also a self-devoted being. The horror of the Shelley’s book is not to be found in the grotesque and mutilated body of the creature, but in the tragic heart of Victor Frankenstein who was devoted only to himself, to the limitless aspirations of the human soul which treat nature and human form as the raw material for will and imagination. It is good to be reminded that in the end it is not the monster who kills him, but the simple fact of his fragile humanity. Frankenstein dies quietly inside Walton’s quarters. The monster himself, the technological creation of a modern Icarus, may continue to survive, but it is a life-in-death – he is, after all, a hodgepodge of corpses. It is a life without limit, but also one without joy. It is an existence of despair. The creature continues alone into the northern cold, ultimately dying by suicide in flame and ash.

The cold is a reminder of the world’s indifference, the place where one’s limit is reached and where the world becomes hostile. In Shelley’s book, it exists as a barrier. Faced with the indifferent north, Walton turns back towards warmth, and humanity. I wonder, then, why is it that I always want to keep forging into it?

The difference is perhaps in this: that I go into the cold not to expand my will, but to feel its limit. The cold is sublime, as Edmund Burke said, it is the most powerful human experience: an encounter with something terrible and wonderful. But the response to the sublime, writes C.S. Lewis, is not to have sublime feelings oneself, but rather feelings of veneration, and of humility. I go into the cold because we are made to be precisely the kind of the creatures who desire to experience the sublime so that I can feel humble and reverent.

The inhospitality of the world draws my own spirit out of me towards what is not me. It is only because of the world’s indifference that I can experience my own body as my home, humble and small. There is a distinction between the world and me; it is not an extension of myself. I end. Because of this limit, I feel the pride of ownership over my own body and spirt. I feel gratitude for my body. My will is not limitless. I cannot conquer the cold around me, but I can freely choose to obey the limits of my own body.

In Shelley, the nightmare occurs not because of human striving but because of self devotion. The cold reminds me that I am not the arbiter of my world. It reminds me that I am vulnerable, and mortal. The pride I feel is that my spirit is able to take joy in this.

And in this the cold is hospitable: it provides me with the occasion to feel reverence. To discover a limit and to find myself up against it, and to find it beautiful. My will is engaged on a deeper level. Rather than try to overcome my limit, I do the moral work of submitting to it without resentment. In doing this I feel myself grow larger on the inside. I live in a world that allows me to feel my own body as itself, to feel my own spirit quicken within me in response to the loneliness around me, to feel my strength increase because of the wind which harasses me and demands that I be equal in courage to its ferocity. Because it does not exist for my comfort, the cold allows me to feel alive. That is the kind of universe we inhabit. Its generosity is to allow us to feel our limit. “Blow, blow, thou winter wind,” writes Shakespeare, “thou art not so unkind as man’s ingratitude.”

This essay was first posted in Quillette.

A beautiful essay, but I still prefer contemplating my limitations living in a physical human body, at the beach on a 90F day. Love your work.

Wow - this is incredible: “Rather than try to overcome my limit, I do the moral work of submitting to it without resentment.” A lot of good work can be done just based on that … thank you for sharing it.